First of a four-part series.

By Rick Vacek | February 27, 2024

Research is full of surprises. Why bother if you know the answers in advance?

But The University of Texas at Dallas has broadened research opportunities in surprising ways with two new programs: Short-term Working Groups, — or SWGs (sounds like swigs) — and an undergraduate research class under the auspices of the Tiny Earth Initiative.

The SWGs pair a faculty member with a cohort of seven to 10 students on a project that includes four in-person sessions of 1½ to two hours apiece.

The program’s goals are to increase opportunities for meaningful faculty-student relationships, positively affect student outcomes and close cultural capital gaps for first-generation students and members of traditionally underrepresented groups in higher education.

Tiny Earth is not part of the standard laboratory curriculum. It assigns students in BIOL3520 and BIOL3203 the task of isolating bacteria from soil samples and then screening the isolates for any that are producing antibiotics.

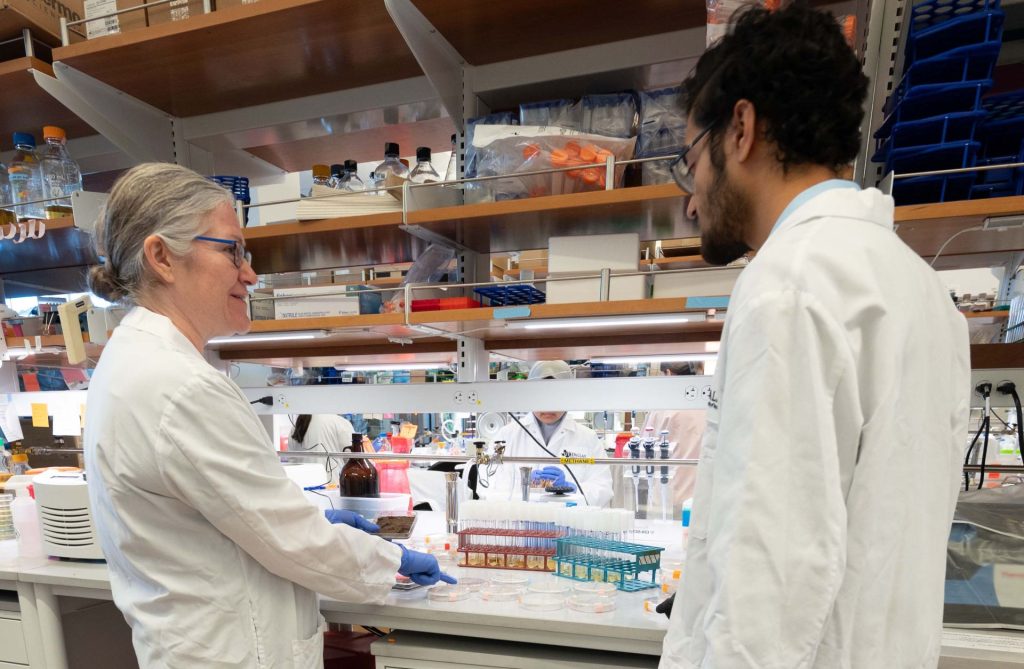

While the research is complicated, the goal is simple: to contribute to the worldwide effort to address the diminishing supply of effective antibiotics. The UT Dallas initiative, begun by Dr. Kelli Palmer, professor and department head of biological sciences and Cecil H. and Ida Green Chair in Systems Biology Science, and Dr. Iti Mehta, assistant professor of instruction in biological sciences, is part of an international network created by Dr. Jo Handelsman of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“You are teaching people skills, like a traditional lab curriculum, but you’re also guiding them through a research project where they’re discovering new things,” Palmer said.

How new? This new. One of her students came to her with a question:

“What would you do with this data?”

Palmer’s response:

“I’ve never seen this data before.”

Her students’ discoveries enabled Palmer to publish a paper about the genome sequences of several bacteria they isolated.

“We’re actually doing scientific discovery here,” she said. “It keeps me thinking and active and also humble, frankly, because people ask me questions and I tell them, ‘I know I’m an expert in this field, but I do not know the answer. We’re going to have to figure this out together.’ It’s very fun for me.”

It’s also fun for students who never had done research previously.

Case in point: Clay Gabel.

Before the spring 2023 semester, Gabel needed four hours of upper-level biology credits to finish his Bachelor of Science degrees in health care studies and biology. His only suitable option was Palmer’s Tiny Earth course.

Then came the first day of class, when he discovered that it was a research course.

“I really am not interested in research, so this will be interesting,” he thought to himself.

“And then I end up falling in love with it.”

He loved it so much, he stayed on as an employee in the Palmer lab.

“It’s a really, really great class,” he said. “A lot of students, they’re like, ‘I really want to get into research, but there are only so many research labs, and there are only so many spaces for undergraduates.’ That Tiny Earth class is a great way to get as many students exposed to research as possible.”

And that exposure can be life-changing.

“It’s a career opportunity for many students in the long term because they might not know yet that it’s something that they want,” Palmer said. “It’s not necessarily the project that you do, but the way that it changes your thinking. How do I make sense of this, this unknown thing that even the instructor hasn’t seen before? How can we work together to tackle this? I think that’s a skill that can be applied broadly.”

The SWGs are having a similar effect. When a group of instructors met in early December to discuss the program’s success, it was a clarifying moment for its originator, Dr. Salena Brody, professor of instruction in psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences and associate director of the UT Dallas Center for Teaching and Learning.

“I’ve become an evangelist for this program,” said Brody, who started it during the spring 2020 semester, paused it during the pandemic and restarted it in spring 2023 before launching new projects last summer.

She has watched the number of classes and participants grow steadily – from seven last summer to eight in the fall and 10 this spring – and is further buoyed when she walks around campus and sees students wearing the “SWG” T-shirts provided by the Center for Teaching and Learning. SWG faculty are trained to be inclusive mentors and to create a sense of community in their sessions by knowing the students’ names and learning more about them.

“Working with students in a non-evaluative context has energized our participating faculty,” she added. “We love seeing the creativity and intellectual risk-taking that is coming from students. The students are getting rich, transformative, skill-building experiences in a short-term, high-impact setting.”

Conversely, working so closely with faculty members is just as energizing for students – it humanizes their mentors. Jacob Pena, a senior biomedical engineering major, said he was skeptical about joining a SWG with Palmer. Now he’s a convert.

“I’ve worked in many labs, but this lab is very different,” he said. “My background is biomedical engineering, so this is all new to me.”

What also makes this particular Palmer lab different is that the students are learning how to make “space bricks” – bricks that could withstand the harsh atmosphere of, say, the moon. The SWG kickstarts new projects and explorations of this nature and sets the foundation for continued mentorship with a faculty member if that happens organically.

Jennifer Bracewell, a UT Dallas master’s student in mathematics and computational biology and a research mentor in Palmer’s lab, started out researching bacteria in Tiny Earth before switching to space bricks. She loves the diversity of majors among the students she assists.

“A lot of them have no lab background – they come in from psych majors.”

JENNIFER BRACEWELL, RESEARCH MENTOR IN DR. PALMER’S LAB

“A lot of them have no lab background – they come in from psych majors,” she said. “I’m just teaching them basic lab skills. We’re having fun. They’re learning so much.”

Palmer likewise stumbled into research. She was a dishwasher for a microbiology lab as a college sophomore, got to do some research and was hooked.

She hopes the Tiny Earth class will have a similar effect.

“There’s a range of reasons why students are in the class, and my job is to give them education but also convince them that they are scientists,” she said. “It’s a mindset. Most of the students in the class are seniors, and I’m one of the last classes on the way out. You’re a scientist. This is you. You are being trained as a scientist. No matter what you do after you go from here, you are a scientist. It’s just engaging them in that process of discovery as opposed to completing tasks to get a grade.”

Discovery. That’s why you bother … because that’s what makes it fun.

Other stories in this series:

Part 2

SWGs Give Students a Taste of Becoming Known